Peace and Order? Peace Messaging in Thai Elections

Duncan McCargo, Saowanee Alexander and Petra Alderman

Thailand’s 2019 election was overseen by a military junta known as the National Council for Peace and Order. For the first time in decades, nobody was killed in election-related violence. Sadly, this was not really a triumph of peace messaging.

In countries where electoral violence is commonplace, one solution can be peace messaging: public campaigns to promote peaceful polling. Thailand has experienced significant levels of electoral violence over recent decades, and faced particular challenges during the contentious 2 February 2014 election, which was held during massive anti-government protests by groups intent on disrupting the polls. One response from grassroots activists was the staging of candlelit vigils calling for a peaceful election.

The Thai experience illustrates both the strengths and weaknesses of peace messaging as a way of framing the prevention of electoral violence.

Peace messaging played some role in reducing election-based violence in 2014, but military-led regimes since then have appropriated the discourse of peace while practicing the suppression of political participation and dissenting voices. That election was subsequently annulled by the courts, and was soon followed by the 22 May 2014 military coup. The junta called itself the “National Council for Peace and Order”, crafting a narrative about disorder and division to legitimate its intervention.

The Thai experience illustrates both the strengths and weaknesses of peace messaging as a way of framing the prevention of electoral violence. It also highlights the need to question what we really mean by violence, and indeed the parameters of the electoral. All this has important implications for understanding how to address potential violence in other elections.

Peace Messaging

Peace messaging covers a wide range of activities designed to encourage voters to engage peacefully in electoral processes – and so to mitigate the threats from electoral violence. Messaging campaigns may involve sporting events, performances and social media, as well as the usual posters and broadcasts. Sometimes peace messaging is initiated by state agencies or electoral management bodies, and sometimes by civil society groups, religious organizations, or even political parties. Locally-initiated peace messaging is likely to be much more effective than campaigns orchestrated by international donors, or even national governments.

The abortive 2 February 2014 election featured a range of civil society-led peace messaging activities, including those of YaBasta Thailand – which organized candlelit vigils around the country – and the Network of 2 Yeses and 2 Nos (yes to elections and democratic reforms, no to military coups and violence), a group of public intellectuals.

Electoral Violence in Thailand

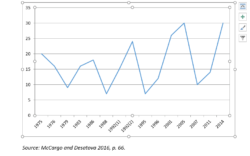

Political assassinations and other acts of physical violence have been a longstanding feature of Thai elections: between seven and thirty people were killed during every election from 1975 to 2014, primarily candidates and canvassers (see Table 1).

Table 1: Election-Related Murders in Thailand, 1975–2014

As the leading scholar Benedict Anderson famously argued, growing violence ironically exemplified higher levels of democracy in Thailand: more election-related murders took place when more was at stake. Electoral violence partly reflected the country’s high murder rate and pervasive provincial gangsterism, as well as growing levels of political polarization after 2001.

As the leading scholar Benedict Anderson famously argued, growing violence ironically exemplified higher levels of democracy in Thailand: more election-related murders took place when more was at stake.

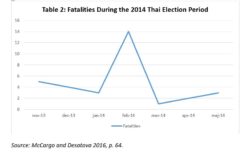

The 2014 election resulted in thirty fatalities, the highest number on record. Eighty percent of those killed during the 2014 election lost their lives in Bangkok, and just twenty per cent in the provinces – a very unusual pattern historically. As Table 2 shows, electoral violence is by no means confined to polling day: people lost their lives in the months prior to the 2014 Thai election, and during the weeks that followed. When fatalities take place over a six month period, how directly can we link these deaths to the polls themselves? Defining levels of electoral violence involves close analysis of events, including cross-checking media reports.

But there’s another problem. Most discussions of electoral violence tend to focus on quantifiable indicators: fatalities and physical harm. Where does this leave structural election violence: suppression of political activity by authoritarian regimes and anti-democratic actors? Structural violence often leaves no physical marks: nobody dies, nobody gets hurt, yet political participation is forcibly suppressed.

This distinction becomes highly relevant when we look at Thailand’s March 24, 2019 election: despite zero fatalities, structural violence was extremely high.

Peace and Order: The 2014-19 Military Junta

The National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO) governed Thailand from 22 May 2014 to 10 July 2019. The preamble to the junta’s 2014 interim constitution offered a justification for the military power seizure, citing the February general election as an example of a failed attempt to prevent unrest, chaos and criminality. At least on the surface, the NCPO was true to its name: after an early period of ad hoc resistance, anti-regime protests quickly ceased and political violence was sharply curtailed. Coup leader General Prayut Chan-o-cha appointed himself prime minister, personifying the militarization of Thailand’s politics.

At least on the surface, the NCPO was true to its name: after an early period of ad hoc resistance, anti-regime protests quickly ceased and political violence was sharply curtailed

The junta deployed a variety of mechanisms to suppress dissent: political activists and critics were summoned to military bases where they underwent spells of 'attitude adjustment'. Those who failed to show up were charged with criminal offenses, often in military courts. Gatherings of more than 5 people were made illegal. Bizarrely, people were arrested for eating McDonald’s (which briefly became a symbol of protest), flashing the Hunger Games three-fingered salute, and even silently, publicly reading copies of George Orwell’s 1984. The first instinct of the regime was to clamp down on all political participation.

The 2016 Constitutional Referendum

The August 2016 referendum on the junta-backed new constitution was a trial run for a return to electoral politics. The NCPO flunked the test. The Election Commission played an extremely partisan role, serving as a cheerleader for the proposed draft rather than overseeing a free and fair plebiscite. Worse still, the regime used its emergency powers to suppress critical voices.

Information shared with voters about the draft was incomplete and distorted, while the 'No' campaign was forced underground, banned from holding events and operating largely online. Voting 'Yes' was presented as the duty of responsible citizens, a loyalty test. Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha refused to say what would happen if the draft was rejected, but hinted that he might simply remain in power indefinitely.

Although the new constitution was approved with 61 per cent support, this was a hollow victory for the junta. 22 out of 77 provinces voted against the constitution, including much of the populous North and Northeast, while the draft was overwhelming rejected in the Muslim-majority southern border region. Five people were killed during the referendum, including a polling station director in the far South; dozens were injured, some in a wave of bombings that hit Southern resort towns, shortly after the vote.

The 2019 General Election

On one level, Thailand’s 24 March 2019 general election was a resounding success: not a single person was killed in election-related violence. Unfortunately the 'orderliness' of the polls resulted directly from tight controls placed by the ruling military junta, which limited campaign activities and even policy statements from political parties during the run-up to the election, and prevented opposition parties from using public venues for their campaign rallies.

Unfortunately the 'orderliness' of the polls resulted directly from tight controls placed by the ruling military junta

At an event organized by Mahidol University and the election-monitoring NGO P-NET in December 2018, 25 Thai political parties pledged to follow electoral laws and campaign peacefully. Palang Pacharat was not among the signatories.

Candidates for the military-aligned Palang Pracharat Party received police escorts and support from local officials throughout the country, courtesies which were not extended to the opposition. Opposition rallies were closely monitored by plain-clothes police officers and military intelligence for violations of election laws.

Worse still, two major opposition parties were dissolved by order of the Constitutional Court, one – Thai Raksa Chart – in the middle of the election campaign. The wildly popular Future Forward Party was slapped with multiple legal challenges: the regime’s 'lawfare' approach culminated when the party was abolished in February 2020. The opposition Pheu Thai Party, despite being the largest party in parliament, was not given the opportunity to form a government: instead pro-junta Palang Pracharat cobbled together an opportunistic 19 party coalition, facilitated by changes to the system for assigning party list seats that were only instigated after the results has been counted.

In short, the pro-military side lost the election, but won the subsequent battle to control parliament. General Prayut Chan-o-cha was upgraded from military dictator to 'elected' prime minister, despite the fact that he has never run for public office. Half of the parliamentarians who voted for him to retain the premiership were unelected members of the Senate, who had effectively been appointed by Prayut himself.

Conclusion

The military junta that seized power in Thailand in May 2014 appropriated the language of peace, whilst deploying repression, intimidation and lawfare to suppress political dissent and curb opposition. The junta rigged the electoral system in order to remain in power after the notional reversion to parliamentary rule. The Thai case illustrates how peace messaging can be abused by authoritarian regimes.

The Thai case illustrates that the absence of electoral violence does not always equal peace, nor does it necessarily herald brighter prospects for democracy.

Sadly, in line with Benedict Anderson’s earlier arguments, reduced violence in the 2019 Thai general election demonstrated that the democratic process had been successfully captured by elite interests. As structural and epistemic violence and repression become more deeply embedded, overt physical violence may actually decline.

The Thai case illustrates that the absence of electoral violence does not always equal peace, nor does it necessarily herald brighter prospects for democracy.

This commentary pulls together research findings from USIP grant SG-477-15, “Peace Messaging in the 2016 Thai Elections”. See our project website.

References

Benedict Anderson, 'Murder and Progress in Modern Siam, New Left Review, 181, May/June 1990.

Duncan McCargo and Petra Desatova, ‘Thailand: Electoral Intimidation’ in Jonas Claes (ed.), Electing Peace: Violence Prevention and Impact at the Polls, Washington DC: United States Institute of Peace Press, 2016, pp. 63–96.

Duncan McCargo, Saowanee T. Alexander and Petra Desatova, 'Ordering Peace: Thailand's 2016 Referendum 2016.’ Contemporary Southeast Asia 39, 1, 2017: 65–95.

Duncan McCargo (ed.), Roundtable, ‘Thailand’s Amazing 24 March 2019 Elections’,’ Contemporary Southeast Asia, 41, 2, 2019. Nine scholars contributed to this roundtable.

Duncan McCargo, ‘Democratic Demolition in Thailand,’ Journal of Democracy, 30, 4, October 2019: 119–133.

Duncan McCargo and Saowanee T. Alexander, 'Thailand’s 2019 Elections: A State of Democratic Dictatorship,’ Asia Policy, 14, 4, October 2019: 89–106.

Authors

Duncan McCargo is Professor of Global Affairs at Nanyang Technological University, and a Visiting Professor at Leeds.

Saowanee T. Alexander is Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Liberal Arts, Ubon Ratchathani University.

Petra Alderman is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the University of Birmingham.